The Outlines of the City (Part 2)

What is the Polis?

The “What is” Questions

The relationship between the city and the political is, at first, unclear. It seems reasonable to assume that the city and the political are intertwined. Why? Politics, understood as living well together, must occur within the city. Strauss begins by approaching the distinct nature of the political through Aristotle's dismissal of Hippodamus.

Aristotle dispensed with Hippodamus' unusually simplified political order by noting that it sought a clarity and simplicity alien to politics. He failed to notice the pecularity of politics, as distinct from the simplicity of mathematics. Strauss notes, “Hippodamus did not succeed in founding political philosophy or political science because he did not begin by raising the question “what is political'' or rather “what is the polis?” The question, and all questions of this kind were raised by Socrates who for this reason became the founder of politcal philosophy.” (1) Chaerephon’s message from the oracle compelled Socrates to turn toward human matters fully. It forced him to ask: What is politics? In dispensing with any oversimplified accounts of the “whole of nature,” Socrates was free of the illusions that burdened Hippodamus. He could then approach the essence of the political in its fullest.

It is in the Aristotle chapter that we approach the “what is” question directly. Strauss writes, “The ‘what is’ questions point to ‘essences,’ to ‘essential’ differences—to the fact that the whole consists of parts which are heterogeneous, not merely sensibly (like fire, air, water, and earth) but noetically: to understand the whole means to understand the ‘what’ of each of these parts, of these classes of beings, and how they are linked one another.” (2) Socrates approached the essential questions first through men’s opinions, the highest of which is the law. But opinions are no longer sufficient when they are contradictory. It is then necessary to return to nature (and Thucydides), a return which Strauss characterizes as an ascent. Still, the question remains: What is the polis?

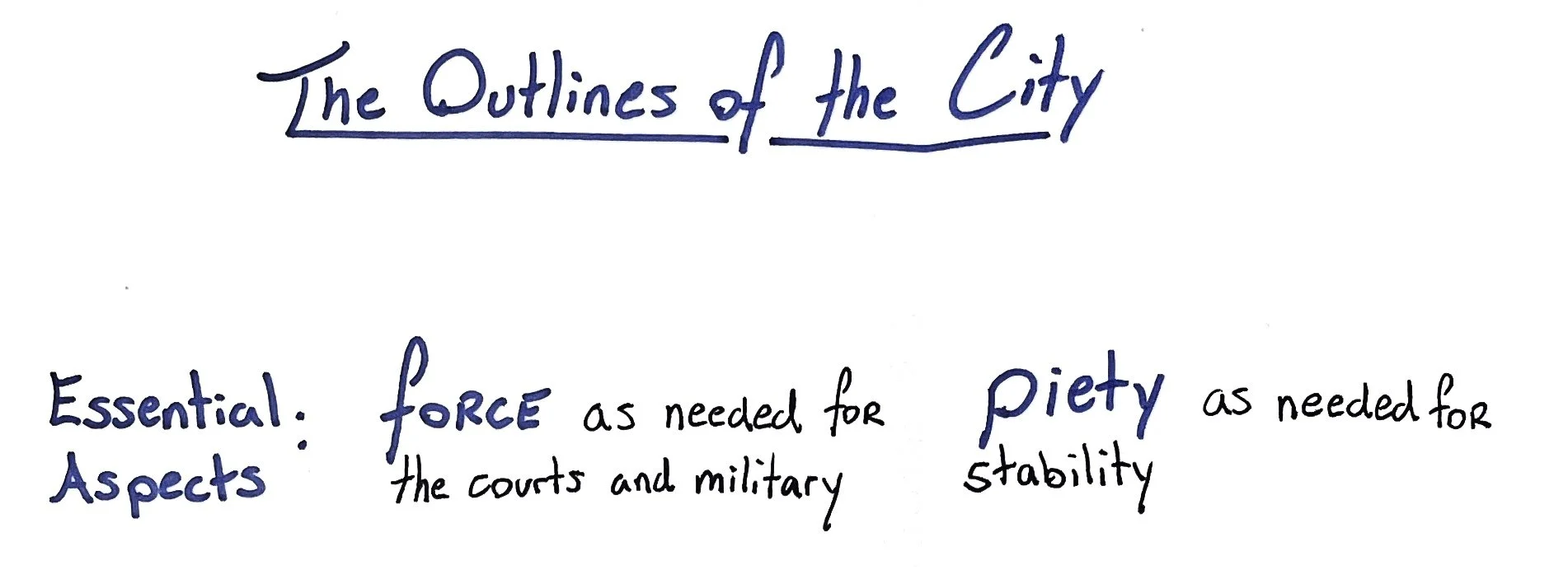

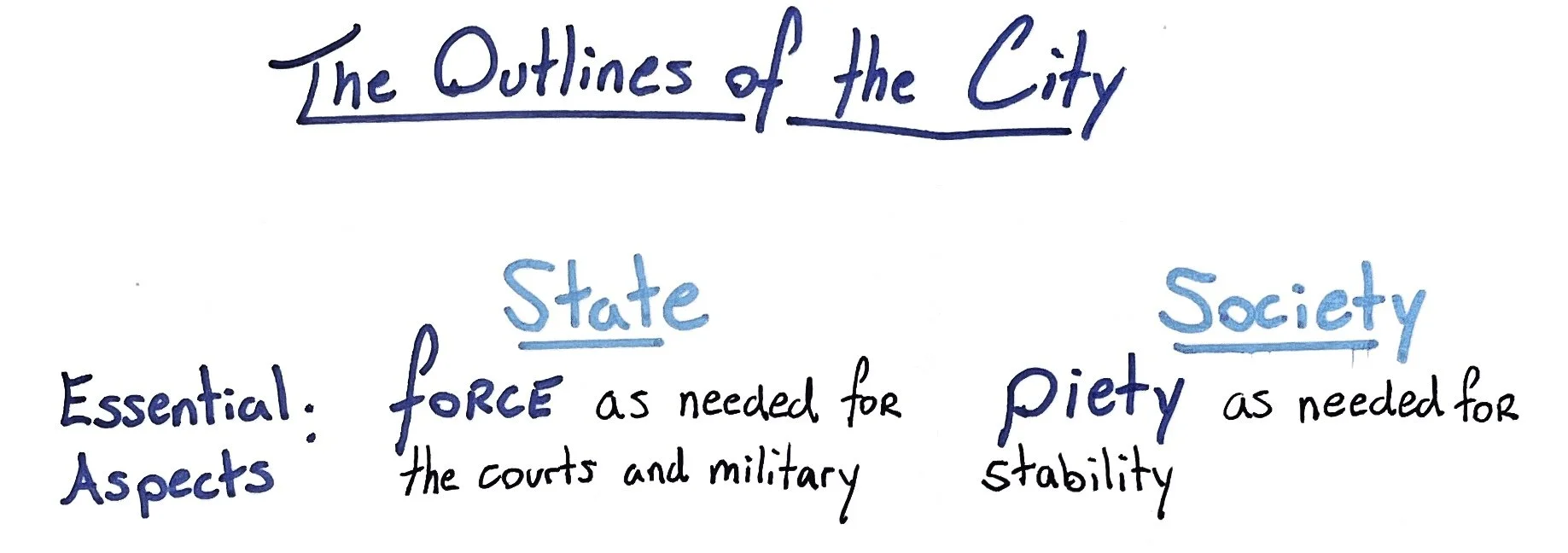

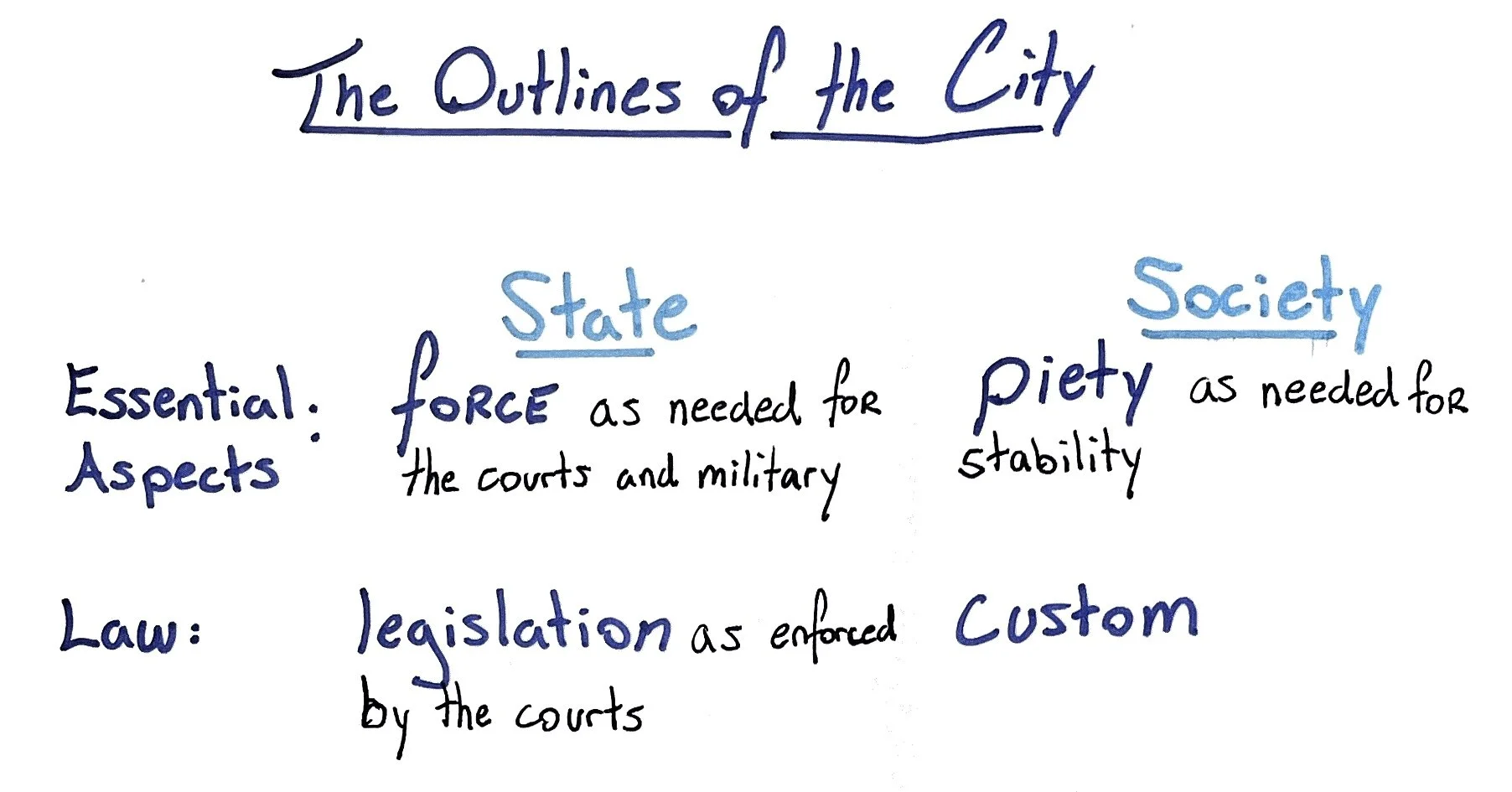

Strauss first points toward the fruit born of the “what is” question in the 9th and 10th paragraphs of the Aristotle chapter, where the reader is sequentially introduced to two aspects of the state: stability and force. Stability requires piety, and force applies both internally (courts) and externally (war). These elements define the unique outlines of the city that we seek to discern.

State and Society

In working with the ancient concept of city is it vital to first comprehend the ancient meaning of the word as distinct from its modern usage. Strauss wrote, “When we speak today of ‘state,’ we understand ‘state’ in contradistinction to ‘society,’ yet ‘city’ comprises ‘state’ and ‘society.’ More precisely, ‘city’ antedates the distinction between state and society and cannot therefore be put together out of ‘state’ and ‘society.’” (3) So, the ancient understanding of the “city” is meant to include not just the governance structure but the culture and norms. That is, it includes both the monopoly on violence and systematic approach to taboo.

Our current understanding of the state does not generally include society. Strauss describes the modern view, saying, “According to that view, the purpose of the city is to enable its members to exchange goods and services by protecting them against violence among themselves and from foreigners, without its being concerned at all with the moral character of its members.” (4) We could say that this modern understanding deliberately negates the state’s responsibility in regulating culture, norms, and taboos. However, as Strauss notes, the word “country”, in modern usage, is often understood to include both state and society. But this word must be used with two notable distinctions: (a) In the city, the town and country are one. And, (b) the alternative to the city is not another city but the absence of civilization, i.e. barbarism. (5)

The Birth of the City

In knowing two unique aspects of the city and its ancient vs modern distinctions, we are left with another question: Why does the city require force and stability? We move from the “What is” quesiton to the “Why” question. An answer is found when examining what it is that piety and force maintain: The law.

The city cannot exist without force and piety. This is, in a way, what it means to be an aspect of its essence: a civilization without force (courts and militaries) and piety (customs and culture), would be something other than a city. As force and piety maintain the law, this also implies that the law is necessary for the city's existence. But Aristotle goes a step further: He claims that the city is brought into existence by its laws. Its birth is one with its constitution.

The claim that the city is brought into being by its constitution can be found in Aristotle’s Politics. In Book III, Aristotle addresses “the puzzle of when we ought to say that a city is the same, or not the same but a distinct one.” (6) After establishing that merely living in the same location is not sufficient to be called a city, and that there is confusion in regarding citizens of the same lineage as a city, Aristotle wrote, “if indeed a city is a sort of community, namely, a community of citizens sharing in a constitution, then, when the constitution becomes a distinct one in form (eidos), that is, becomes different, it would seem that the city too cannot remain the same.” (7) To clarify: If a city is a community of citizens sharing in a constitution, then a change in constitution would mean the creation of a new city. This would fall in line with the claim that the city is a man-made entity, as it is brought into being by a man-made constitution (i.e., the constitution is an ontological necessity). But this essay is not written primarily with regard to Aristole’s Politics but rather to The City and Man of Leo Strauss, a separate philosophical work in its own right.

Partisans and Patriots

In The City and Man, Strauss’ first acknowledges the seeming absurdity of the claim that a city with a new constitution is a new city, as it “seems to deny the obvious continuity of a city in spite of all changes of regime.” (8) That is, it seems to deny the continuity of matter (the people, the place) while focusing on the discontinuity in form (regime). But he asks for the reader to pause and consider that Aristotle’s assessment is closer to our experience than it may initially seem. Strauss then refers to an example from the Politics, where a democrat may deny that the actions taken by a tyrant are, in fact, the actions of the city. “The democrat, the partisan of democracy, implies that when there is not democracy, there is no city.” (9) He continues, “Let us say then that for the partisan of any regime in the city ‘is’ only if it is informed by the regime which he favors. There are other people, the moderate and sober people, who reject this extreme view and therefore say that the change of regime is a surface event which does not affect the being of the city at all… Let us call these men patriots.” (10)

Strauss clarifies that Aristotle disagrees with both assessments. During a regime change, the partisans claim the city ceases to be, and the patriots claim there is no change. Strauss shows that Aristotle finds the middle ground. He wrote, “the city (according to Aristotle) does not cease to be but becomes another city—in a certain respect, indeed in the most important respect; for through a change of regime the political community becomes dedicated to an end radically different from its earlier end.” (11) That the city changes in the most important respect implies it is unchanged in less important respects. Among these unchanged aspects are the matter (people, place) which I referred to earlier.

All this to say that the city takes its form in its constitution, but its matter exists prior to its form. If we accept that a group of people merely living in the same place without any shared aim or identity does not qualify as a city, then it is true that a city is born (i.e., takes its form) with its constitution—with the law.

Notions of Justice

In further understanding Aristotle’s claim of regime change, Strauss asks the reader to consider the notion of loyalty. The loyalty that is demanded of a citizen is to the country informed by the regime. I.e., the matter in its current form. Claims of loyalty only to the matter itself but against its current form (consider a communist living under a liberal democracy) are not recognized and often treated with outright hostility. But, when a regime is in a state of decay, calls for its transformation into a state another regime (such as calls for a new communist regime under a failing liberal democracy) become publicly defensible. (12) But why does the state of decay make the apparent disloyalty justifiable?

Answering this question requires us to distinguish between legality and legitimacy. What is legal, Strauss wrote, derives legitimacy from a specific notion of justice (i.e., the notion of justice accepted by the majority of society). (13) The state of decay brings the old notion of justice into question, and thereby delegitimizes the previous regime. This delegitimzation allows for calls of regime change; which were previously indefensible.

Importantly, this discussion of legitimacy brings our discussion of the city a layer below the law. A common understanding of justice is required for respect of law.

Yet, this is all in regard to notions of justice, notions which are almost surely misconceptions. What about the idea of justice? I.e., true justice—the idea in the platonic sense. Is the idea of justice an aspect of the city?

Socrates argues that justice is of natural origins. The sophists disagree and thereby place it within convention. That is, the sophists would argue that justice—i.e., the justice of Thrasymachus that protects the weak from the strong—is found only in a city. But is this justice even worth the name? Socrates doesn’t think so.

Socratic justice, i.e. “the art of assigning to each what is good for his soul and as the art of discerning and procuring the common good,” (14) is found in no city. (15) Strauss accepts the Socratic definition of justice (16) and therefore accepts its natural origins. That is to say he agrees there is a true Platonic idea of justice—it is not just something that humanity made up, but rather exists in the same way that numbers exist. Therefore, the justice found in man’s cities is only a single perception of it, as the 2-demensional viewer of the cylinder sees either a circle or a rectangle. The 3-demensional cylinder is not found in the 2-demensional city, as true justice is not found in cities of men.

It is precisely the just which gives the political its relevance. It is the just which allows for the common good; “justice is the common good par excellence.” If justice is natural, then politics is a noble pursuit. If it is not, politics is only rhetoric. (17)

Force Overpowers Reason

As alluded to earlier, Strauss addresses the second aspect of the city in the tenth paragraph of the Aristotle chapter: force. He begins strikingly, “The very nature of public affairs often defeats reason.” (18) This aspect of the city remains relatively unhidden in modernity, as the government is commonly understood as the monopoly on violence. He elaborates with an example of unjust slavery in Aristotle’s politics, where force can overpower an independent rational man into servitude. He then continues, “Plato… expresses the same thought more directly by admitting, with Pindar, that superiority in strength is a natural title to rue. From this we understand why the nature of political things defeats to some extent not only reason but persuasion in any form and one grasps another reason why the sophistic reduction of the political art to rhetoric is absurd.” (19)

Strauss continues by noting the distinction between Gorgias and Xenophon, noting that the former possessed only the rhetoric while the latter held “the full poltical art.” Finally, and most strikingly, Strauss comments on the transition from the Aristotlelian Ethics to the Politics. “The very same thought—the insufficiency of persuasion for the guidance of ‘the many’ and the necessity of laws with teeth in them—constiutes the transition from Aristotle’s Ethics to his Politics.” (20) That is, the transition between works is marked by the inclusion of violence.

Stability & Piety

While it is in the Aristotle chapter where Strauss first brings up the City’s need for reverence, it is in the following paragraph that he discusses the connections between gods, laws, and stability. Strauss approaches the lesson once again through Aristotle’s distinction with Hippodamus. He writes, “He (Aristotle) is much less sure than Hippodamus of the virtues of innovation. It seems that Hippodamus has not given much thought to difference between innovation in the arts and innovation in law, or to the possible tension between the need for political stablity and what one might call technological change.” (21) Continuous change in law means a city in permanent revolution, something antithetical to stability. If stability is in the nature of the City, then continuous innovation in law is also antithetical to the city itself. But why is stability—or, at least, the need for stability—a distinct aspect of the city’s nature?

We have established that a city is only customary, i.e. it is a human-made entity rather than a natural one, and it gets its structure from its laws. And so, the law is required for the city’s continued existence. As laws in the city include custom, they require time to maintain their power. (22) In sum, the city gains its structure from custom (and law), which gains its power from stability (and force).

But the word “custom” needs unpacking. How are customs maintained? Here, taboo serves a functional purpose: it prevents citizens from discussing what will destabilize their city. Discussing taboos is impious, as it threatens the gods of the city. Strauss continues, “The law, the most important instrument for the moral education of ‘the many,’ must then be supported by ancestral opinions, by myth—for instance, by myths which speak of the god as if they were human beings—or by a “civil theology.” (23) So, the law must gain its status from something sacred, and uses taboo to maintain its sacrosanctity. For the city, then, piety is a necessity; impiety erodes its very being.

Foreign Policy

In the final chapter ‘On Thucydides’ War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians,’ Strauss approaches the anarchy (i.e., the absence of higher authority) found in foreign relations. This absence of authority is paired with an absence of ideals, as persuasion falls away in favor of compulsion. This is seen most clearly in the Melian Dialouge, to which Strauss dedicated an entire section of the chapter. It is in the Melian Dialouge where realist logic reigns supreme.

In reading Thucydides, one may initially conclude that the Sicilian disaster, which immediately follows the Melian dialouge, is a divine punishment for the immodesty presented by the Anthenians in Melos. But Strauss shows this is not quite true. The Athenians fell in Sicily because of the most tyrannical aspects of the demos, which prevented their leaders from acting in the public’s best interest in fear of losing their (private) heads. (24) This lesson, combined with the faults of the overly pious Nicias, show that in foreign relations there is no place for custom or persuasion. Those only arise in a hierarchy that is absent between cities in the Peloponese. And without piety, there is only force.

Conclusion

To recount: The Latin Words for "true" and "what is made" are the same. This rediscovery implies one can only know what one can make. One can use this information to arrive at two distinct conclusions: (1) Pessimitically, only god knows all, or (2) optimistically, we can know what we have made. The optimistic conclusion brings good news to the student of politics. We have made the city. Therefore, we can know the city.

The question "what is the polis?” initially reveals two essential elements—Force and Piety—and an important convergence of concepts, as the City predates the distinction between state and society. As the city includes both state and society, it is most similar to our concept of country. Protecting the law is necessary for the city because it is the law that brings the city into being. This is first addressed by Aristotle, and Strauss clarifies that the ancient philosopher acknowledged the sameness of matter (place, people) but is referring to the creation of form (regime). Still, without form the city is not at all. It is therefore fair to say that law brings a city into being. The state aspect (legislation) of the law requires force, and the society aspect (custom) of the city requires law.

Beneath legality is legitimacy. What is legal derives its legitamacy from a specific notion of justice (i.e., what the majority of society regards as just). This notion of justice is distinct from the idea of justice (platonically understood), which is not an aspect of the city.

Finally, one might add that between cities there is no piety, only force. The realist logic of international relations is presented in Strauss’ analysis of the Melian Dialouge and its consequences. This is felt most poignantly in the fate of poor Nicias, the Spartan in Athens.

Strauss, The City & Man (1963). On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 7

Ibid. On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 8

Ibid. On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 16

Ibid. On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 19

Ibid. On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 16

Politics 1276a20

Politics 1276b1

Strauss, The City & Man (1963). On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 31

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 32

Ibid.

Ibid. On Plato’s Republic ¶ 39

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 10

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. On Aristotle’s Politics ¶ 9

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. On Thucydides’ War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians ¶ 53