Dmitri Karamazov & Newcomb's Problem

Update: Here is an article from Vice about physicists and philosophers redeveloping interest in retrocausality, which I argue for in this essay. Here is Eric Weinstein’s response to the Vice article. I believe, although I’m not certain, that the second number he refers to signifies dimensions of reality. The first number denotes temporal dimensions, and therefore potential futures. I.e., a (1,3) would refer to our common conception of a 3-dimensional reality with a single future.

“Oh, sir! I feel afraid of driving you. Your talk is so strange.”

But Mitya did not hear. He was frantically praying and muttering to himself.

“Lord, receive me, with all my lawlessness, and do not condemn me. Let me pass by Thy judgment … do not condemn me, for I have condemned myself, do not condemn me, for I love Thee, O Lord. I am a retch, but I love Thee. If Thou sendest me to hell, I shall love Thee there, and from there I shall cry out that I love Thee forever and ever … But let me love to the end … Here and now for just five hours … till the first light of Thy day .. for I love the queen of my soul … I love her, and I cannot help loving her. Thou seest my whole heart… I shall gallop up, I shall fall before her and say, ‘You are right to pass on and leave me. Farewell and forget your victim … never fret yourself about me!’”

— Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

An Ostrich-like Introduction

Undoubtedly, the quote above is somewhat startling, and by no means do I intend to leave the reader dazed and confused. But I must dismiss it momentarily and discuss a puzzle that seems entirely rational—far from the deranged cries of our poor friend Mitya. Let the reader be assured he will be led back to the quote soon enough when it is time to justify Dostovesky’s deranged ramblings.

This essay is inspired by Robert Nozick’s Newcomb’s Problem and the Two Principles of Choice. Nozick begins with an approach he describes as “ostrich-like.” He first puts forth a problem, then disregards it to discuss contemporary decision theory, and finally removes his head from the sand to face the problem directly. Likewise, I will begin with a discussion of faith in The Brothers Karamazov, discuss Newcomb’s Problem in relation to virtuosity, and finally return to apply Mitya’s love of God under the most extreme circumstances.

I must issue an additional caveat: I have very little interest in Newcomb’s Problem for its own sake. Instead, I’m interested in the problem as it relates to a rational faith. Therefore, my intention in this essay is to use The Brothers Karamazov to instruct us on how Newcomb’s problem provides insight into this topic. I suppose, albeit only coincidentally, this essay also serves as an analysis of Calvinism. Or it doesn’t. I’m no religious scholar.

Faith in The Karamazov Family

The Brothers Karamazov is the story of a patricide. It's a murder mystery, effectively, where each character embodies a deeper philosophical perspective. In the beginning, three (possibly four) brothers return home for different reasons. The oldest is Dmitri—or Mitya, for short. He is passionate and sinful, irrational and exuberant. His intemperate nature leads to sinfulness, and his sinfulness leads to his suffering.

Ivan, the middle child, is a young intellectual with cutting and effective arguments against religion and faith. He accepts that being itself may imply a creator, but he rejects this creator and his intentions. Just prior to his famous monologue, The Grand Inquisitor, Ivan considers the life of a five-year-old girl who is beaten and tortured by her parents. He claims that no salvation and eternal bliss can justify this cruelty.

Alyosha is the youngest brother and the foil to Ivan. He is a disciple of the wise Father Zossima at the local monastery, where the friar has encouraged him to leave contemplative life in favor of a more worldly existence. Aloysha has a simple faith in God and genuine love for humanity. He is not necessarily rational, like Ivan, but holds immense wisdom he often struggles to articulate.

Dostoyevsky uses these characters to justify his Christian faith. He does so through character arcs and rational arguments, often allowing the former to overrule the latter. I find him to be extremely convincing because he accurately represents a perplexing pattern: those with unbending faith seem to live better lives than those without. They seem to have a more positive effect on those around them, regardless of their inability to win rational arguments.

There is a subtle debate between philosophers John-Paul Sartre and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. In an interview with Lex Fridman, Harvard philosophy professor Sean Kelly lays out each side. Sartre wrote, “If there is no god, then all is permitted,” and Dostoyevsky agrees. Both The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment seem to concede this point. Dostoyevsky never explicitly says so, but his novels carry this line of thought a step further. The stories seem to respond, “Yes, if there is no god, then all is permitted. But look at our lives; all is not permitted! When you commit terrible acts, such as the murders in each novel, your life becomes unlivable. Therefore, God is real.”

The questioning, of course, could end there. But I’d prefer to take the discussion a step further. In considering the existence of God, Dostoyevsky identifies phenomena that loosely define the edges of a moral order—namely, guilt and insanity. Ivan (and Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment) suffer mental and physical illness from their guilt; both anguish so intensely that they fall to insanity.

If one acknowledges the existence of this phenomenon in reality, then he has good reason to consider a natural or divine moral order. Please recall what our friend Fyodor attempts to establish: All is not permitted. Therefore, there is a cause for the non-permittance. Dostoyevsky believes the cause is something divine, but the reader need not make that jump. He or she is free to believe the phenomenon outlines a natural moral order rather than a divine one.

Either way, another question follows: How should we live within that moral order? That's what I hope to get at here with Newcomb's problem.

Notes on Newcomb's Problem

In Nozick’s Newcomb’s Problem and the Two Principles of Choice, he gives the following description:

Suppose a being in whose power to predict your choices you have enormous confidence. (One might tell a science-fiction story about a being from another planet, with an advanced technology and science, who you know to be friendly, etc.) You know that this being has often correctly predicted your choices in the past (and has never, so far as you know, made an incorrect prediction about your choices), and furthermore you know that this being has often correctly predicted the choices of other people, many of whom are similar to you, in the particular situation to be described below. One might tell a longer story, but all this leads you to believe that almost certainly this being's prediction about your choice in the situation to be discussed will be correct.

There are two boxes, (Bl) and (B2). (B1) contains $1000. (B2) contains either $1,000,000 ($M), or nothing. What the content of (B2) depends upon will be described in a moment.

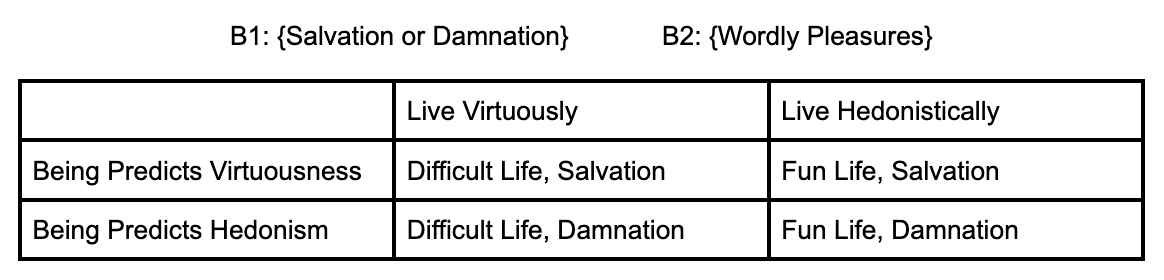

(B1) {$1000} (B2) {$M or $0}

You have a choice between two actions:

(1) taking what is in both boxes

(2) taking only what is in the second box.Furthermore, and you know this, the being knows that you know this, and so on: (I) If the being predicts you will take what is in both boxes, he does not put the fiM in the second box. (II) If the being predicts you will take only what is in the second box, he does put the $M in the second box.

The situation is as follows. First the being makes its prediction. Then it puts the $¡¿ in the second box, or does not, depending upon what it has predicted. Then you make your choice. What do you do?

I will focus on a slight variation of the problem discussed in Nozick's work, of which I must clarify a few details below.

Like Nozick’s description, this game also features two boxes and a seemingly omniscient being. It will also maintain the same general rule structure: The player can either take only B1 or both B1 & B2. If the being predicts only B1, it will leave the large prize in B1. If the being predicts both B1 & B2, it will leave B1 empty.

I will even go so far as to say that all previous 1-boxers have found the large prize in B1, and all previous 2-boxers have found B1 empty. That is, the being has never been wrong. Importantly, a friend with your best interest in mind can see the content of the two boxes and urges you to take them both. A matrix depicting Nozick’s description can be seen below.

Unlike Nozick’s description, this essay will not focus on money. Instead, the choices and prizes will be of a moral and spiritual nature, respectively. In place of $1000, B2 will hold worldly pleasures. In place of either $1M or $0, B1 will hold either salvation or eternal damnation. Choosing two boxes, in this instance, is equivalent to accepting one’s eternal fate and deciding, if it is already determined, it is better to enjoy the pleasures of life than to forgo them.

One could imagine the 2-boxer has recently binged The Good Place with Kristen Bell, Jameela Jamil, and Ted Dansen. He was so taken by the premise that he felt he must attempt it in his own life. Or, of course, he could simply be following the logic presented in the next section. Choosing one box is equivalent to living a virtuous life sacrificing earthly pleasures in hopes of receiving eternal bliss.

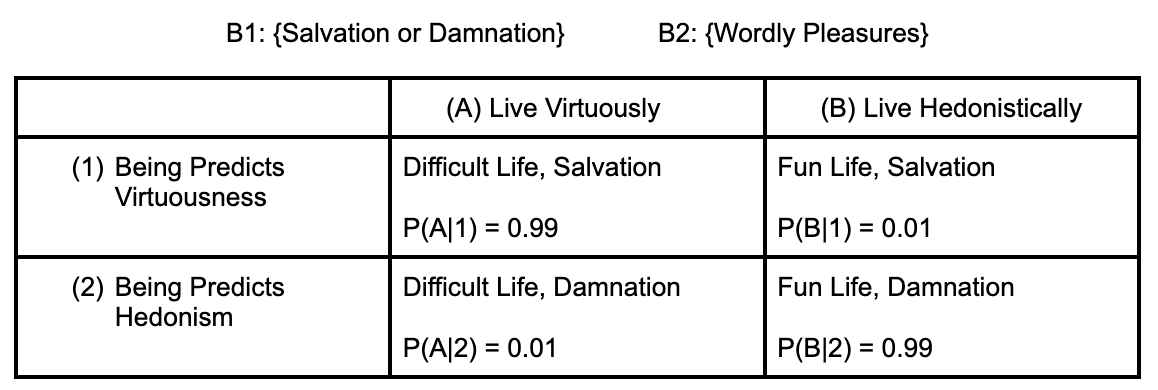

A matrix depicting the moral version of Newcomb’s Problem is shown below.

Alternatively, the matrix can be structured as follows:

As I mentioned earlier, this version of Newcomb’s Problem is an attempt to gamify the Calvinist dictum of predestination. Calvinists believe that God granted eternal salvation to a select number of souls at the beginning of time. Regardless of God’s prediction, nothing an individual does during their mortal life can alter their fate. However, God’s prediction is based on an evaluation of one’s moral character. So, those whom he granted salvation will be more inclined to behave virtuously than those he did not. As I also mentioned earlier, this essay is in not meant to be an evaluation of Calvinism. If it is, that is only coincidental.

A common objection may be that a virtuous life is preferable to the hedonistic one, and this may well be true. But, for the sake of this puzzle, I assume that the indulgencies of the 2-boxers are preferable to the abstinence of the 1-boxers.

Three Assumptions

The first, as discussed above, is that Newcomb’s Problem can be reinterpreted to fit the Calvinist predestination doctrine. But I'm going to make a slight twist: the symptoms of salvation or damnation will begin manifesting before death. This concept is present in The Brothers Karamazov, where the characters experience spiritual consequences in their lives and in a C.S. Lewis quote that will later be of importance. Finally, the third assumption is that literature, and Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov, provides access to phenomena difficult to access through propositional arguments. The implications of these assumptions will allow for an examination of the Calvinist Newcomb's Problem.

Dash the Cup: Ivan & 2-Boxism

The 2-boxer's case is simple: God has predetermined who will enter the gates of heaven and who will fall to eternal damnation. If this is the case, the player's actions do not affect the outcome. So, regardless of God's decision, it is preferable to live a hedonistic life.

This line of reasoning uses the Dominance Principle, which states: If there is a partition of states of the world where action A weakly dominated action B, then A should be performed rather than B. Action A weakly dominates action B for person P if and only if, for each state of the world, P prefers the consequence of A to the consequence of B, or is indifferent between the two consequences.

As seen in the above matrices, hedonism is always preferable to virtue if the outcome is predetermined. If God predicted virtue, then one can add a life of hedonism to his salvation. On the other hand, if God predicted lawlessness, then one might as well enjoy a few worldly pleasures before his damnation.

Most importantly, the 2-boxers emphasize that the decision is made at the beginning of time and cannot be changed. As Calvinists understand it: When they began their life, God knew them fully and determined whether or not they were fit for his kingdom. They may also emphasize our friends. According to the game’s description, we have a friend (one with our best interest at heart) who knows God’s decision and encourages us to engage in the garden of earthly delights. You may imagine a friend urging you to join him at the bar when you should be praying or another planning a trip to Vegas for the same weekend as your meditation retreat.

Among the Karamazov Brothers, the 2-boxer position is embodied in Ivan Karamavoz. Rather than pointing towards predestination, as occurs in the Calvinist doctrine, Ivan argues that the suffering of life is so great that living is not worthwhile. As you’ll recall: Ivan tells the story of a five-year-old girl who is beaten and tortured by her parents. He claims that no salvation and eternal bliss can justify this cruelty. So, rather than arguing that his fate is predetermined, Ivan rejects the game entirely.

It is his next move that follows the Dominance principle. Regardless of his anger towards God, Ivan admits that he cannot help but have a zest for life. He finds himself overcome by the pleasures life has to offer. Even if this life is not worthwhile or justifiable in any real sense, Ivan decides he might as well enjoy himself while he’s here.

Below, Ivan tells his brother Alyosha that he wishes to drink from the cup of life while he still has his youth. But the second his youth is lost, he will lose interest and turn away from it all.

“Do you know I’ve been sitting here thinking to myself: that if I didn’t believe in life, if I lost faith in the woman I love, lost faith in the order of things, were convinced in the fact that everything is a disorderly, damnable, and perhaps devil-ridden chaos, if I were struck by every horror of man’s disillusionment—still I should want to live, and having once tasted the cup, I would not turn away from it till I had drained it! At thirty though, I shall be sure to leave the cup, even if I’ve not emptied it, and turn away—where I don’t know. But till I am thirty, I know that my youth will triumph over everything—every disillusionment, every disgust with life” (Dostoyevsky 213).

— Ivan Karamazov

Ivan is a 2-boxer because he accepts the weakly-dominating actions of worldly pleasure, if only for a short while. Interestingly, Ivan's fate, the fate common to 2-boxers, is met even before death. He is struck with overwhelming guilt by his role in his father’s murder and falls into an insanity that is not redeemed. The difference is that his approach to worldly pleasures does not cause his decline, at least not directly. Instead, it is his refusal to take responsibility for those he influences. The connection between indulgence and irresponsibility is unclear. For now, I will only note that Dostoyevsky combines the two within the same character.

Why ain'cha saved? Alyosha & 1-Boxism

The 1-boxer case is even more succinct. David Lewis wrote, "If you 2-boxers are so smart, why ain'cha rich?" This argument is useful and convincing but ultimately unsatisfying. It clarifies the irrationality of the 2-boxer argument but punts the why question.

It is convincing as an exposure of 2-boxism. If all the 2-boxers leave with $1K and the 1-boxers with $1M, something about 2-boxism is inadequate. It is useful because it removes the player's focus from models and logic and brings his attention back to reality. But the argument is unsatisfying because it does not provide an explanation.

The moral rendition of 1-boxism is: If you 2-boxers are so smart, why ain'cha saved?

Surely a clearheaded 2-boxer would concede that an eternity in the Kingdom of Heaven is preferred to a short period of earthly pleasures. Yet, their strategy has uniformly left their players with the less preferable outcome.

Novick evokes the Expected Utility Principle, which includes probability in decision-making. According to the expected utility principle, the decision-maker should perform the action with maximal expected utility. Returning to our original matrix, we can the following adjustments:

Nozick provides a clarifying example. Imagine a student-athlete who may or may not have a deadly disease. The disease is determined genetically at birth and manifests later in life. As he approaches the completion of his undergraduate degree, he must decide to pursue either a career in academia or professional baseball. He would prefer academia to baseball, although only slightly. But, those who pursue intellectual endeavors are more likely to have this fatal disease. It would be ridiculous for him to choose baseball for this reason, as his genetics have already been determined. His decision does not affect the outcome. He should, therefore, choose the action that weakly dominates.

Among the Karamazov Brothers, 1-Boxism is embodied by the hero: Alyosha. On the narrator's account, it seems Alyosha has a lucky draw. He was naturally predisposed to reject worldly pleasures to pursue life at the monastery. This predisposition, in all likelihood, led the omniscient being to successfully predict his 1-boxist behavior. Even more so, Alyosha is overcome by the 2-boxist arguments of his more rational and articulate brother, Ivan. He cannot offer a response other than his own way of being and its consequences. But in the end, that is enough. Ivan is damned, and Alyosha finds salvation. The 1-Boxer may argue that no other response is needed. If Ivan is so smart, why wasn't he saved?

In sum: It seems that the 2-boxer is right according to his model of reality. But the 2-boxers are damned, and the 1-boxers are saved. So, one may conclude that the 2-boxer’s model is flawed. But how? The character ark of the eldest Karamazov gives us a clue.

Dmitri Karamazov & 1-Box Extremism

In many ways, Alyosha’s task was easy. He was naturally predisposed to 1-boxism and, therefore, safe to assume he was granted salvation at the beginning of time. He had the soul of a saint and easily lived as one. But what of those with the souls of sinners?

If the content of B1 is determined at the beginning of time, and a player begins life with an inclination toward sin and debauchery, that may be enough to conclude he is damned. Shouldn’t he then, without much fuss or commotion, dive head first into worldly pleasures?

Ivan refers briefly to a Greek poem, The Wanderings of Our Lady through Hell, where Mary visits the depths to see the sinners and their torment. Ivan notes that she sees a sign, “‘these God forgets’—an expression of extraordinary depth and force” (Dostoyevsky 229). Does the sinner, whose soul pulls him toward sinfulness, not have all the information he needs to deduce his damnation? Can he not already recognize that it is he whom God forgets?

That may have been a bit dizzying, but I do not intend to hide my hypothesis. The proposition can be understood in three claims. (1) God makes his judgment based on the quality of the player's soul or essence. (2) The player's soul dictates which activities he finds pleasurable or unpleasurable. Therefore, (3) the player could reasonably conclude God's prediction from that which brings him pleasure.

The first claim requires a few underlying assumptions: (1) The player has a soul or essence. (2) God has access to this essence at the beginning of time, and (3) it is this soul or essence which God uses to predict behavior. Within the context of Calvinism and Newcomb's Problem, the first assumption seems quite reasonable. If the player lacks a soul or essence, there is nothing left to enjoy salvation or anguish in its absence. The game accepts the afterlife; therefore, it must accept an aspect of being that can participate in it. That aspect can be defined as the soul.

The second assumption gets at the root of the confusion. Souls are often understood as the aspect of humanity that is eternal—that is, outside of time. This hints at the possibility that God is making his prediction in eternity, and the player interprets his fate in temporality. This assumption is important, and I’ll return to it later. For now, it is only essential to assume that both the soul and the omniscient being dwell in eternity and that this would allow the omniscient being access to the soul at any point in the temporal realm.

The second claim—that the soul dictates which activities one finds pleasurable or unpleasurable—is inspired by Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics. In Book X, during the discussion on pleasure, he wrote, “with regard to virtue of character the biggest thing is enjoying what we should and hating what we should” (Aristotle 1172a21). Aristotle claims character determines what an individual likes or dislikes and that to be virtuous is to like and dislike the right things. I’m extending this claim to say that character is underlied by the soul. The third claim is an inference from claims one and two.

If I lost the reader during the discussion on souls and eternity, I apologize. We may return to more solid ground to say: Those who have reason to believe that B1 is empty should take both boxes. The above argument only uses inclinations to make predictions on what is in B1.

In the Calvinist rendition: Those who are inclined toward sainthood should take only B1; those who are inclined toward sin should take both B1 and B2. But what of those who are inclined to sin—who have every reason to believe that B1 holds damnation—but take one box anyway? Or, from the secular perspective, there are those with reason to assume that B1 is empty, but take one box all the same. Is there anything to learn from these 1-Box extremists?

The aforementioned 1-Box extremism is the position taken by the eldest Karamazov Brother, Dmitri. 1-Boxism is a position of faith, and an empty B1 means eternal damnation. In the quote at the beginning of the essay, Dmitri claims he will maintain his 1-Boxism despite all reasons to believe that B1 is empty. That is, he will love God from hell.

“If Thou sendest me to hell, I shall love Thee there, and from there I shall cry out that I love Thee forever and ever … ‘You are right to pass on and leave me. Farewell and forget your victim … never fret yourself about me!’”

It is with Dmitri that Dostoyevsky makes his most interesting claim, one that seems to contradict the rules of Newcomb's Problem. Despite a life of sin and lawlessness, Dmitri is saved. His prayers, however turbulent and incoherent, are answered. Dmitri experiences a spiritual transformation.

It isn't easy to make any claim regarding spiritual transformation. People are generally skeptical or confused, and those who speak of it typically have trouble defining it clearly. For this essay, I will only note that Dmitri regained his sanity, and his inclination toward a life of sin and lawlessness quickly left him. I will also note the similarity of this description to the spiritual transformations defined in the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous and the recent Johns Hopkins Psilocybin experiments under Dr. Roland Griffiths. Finally, I will note that this description fits well with the assumption of Aristotelian Character.

A claim of spiritual transformation is especially challenging to make propositionally (assuming the reader did not fully buy my discussion of souls and eternity). But readers seem to accept this outcome as valid. That is, they do not put the book down and say that the plot no longer makes sense. This tips off a common intuition that the story has some connection to reality.

Regardless, an additional assumption is required to make sense of spiritual transformation. If Dmitri is capable of reversing a decision at the beginning of time, then a traditional linear model of time will no longer be adequate.

An Additional Assumption: Temporality and Eternity

Newcomb's problem is troublesome for notions of free will. The being makes its decision before the player acts, and it is always correct. Yet, the player still has the choice. How can that be? One explanation is easy enough: the world is deterministic; free will is an illusion. Or, if determinism makes the reader uncomfortable, perhaps only this game is deterministic. The rest of the world can be left up to debate.

One can explain determinism materialistically, where DNA or physical structure determines personality and behavior. But, for the sake of this game, we are accepting the existence of an afterlife and, therefore, an aspect of being that is non-material. This allowance provides an opportunity for an alternate approach.

If we again assume that souls are eternal and our experience is temporal, the player's choices are merely material manifestations of their souls. In this explanation, our decisions simply reveal our nature. Person A is a 1-boxer; person B is a 2-boxer. They are and always have been. When faced with Newcomb's Problem, their decisions only express their soul's disposition. This interpretation is also deterministic, given that the soul remains unchanged.

The temporal-eternal distinction also accounts for the omniscient being's ability to predict outcomes. God is not subject to linear time. It exists eternally and can judge eternally. No further explanation is needed.

I proposed a theory in class that the others quickly rejected. The idea—which, I acknowledge, initially seems unlikely—was that our present actions affect past circumstances. But, the situation is better understood with the temporal-eternal distinction. Our temporal decisions are still deterministic but determined by our eternal nature. In class, I included a quote from C.S. Lewis, which said the following:

“Son,' he said, 'ye cannot in your present state understand eternity...That is what mortals misunderstand. They say of some temporal suffering, "No future bliss can make up for it," not knowing that Heaven, once attained, will work backwards and turn even that agony into a glory. And of some sinful pleasure, they say, "Let me have, but this and I'll take the consequences": little dreaming how damnation will spread back and back into their past and contaminate the pleasure of the sin. Both processes begin even before death. The good man's past begins to change so that his forgiven sins and remembered sorrows take on the quality of Heaven: the bad man's past already conforms to his badness and is filled only with dreariness. And that is why...the Blessed will say, "We have never lived anywhere except in Heaven,” and the Lost, "We were always in Hell." And both will speak truly.”

― C.S. Lewis, The Great Divorce

Justifying Dmitri

1-boxism dispenses the preferable outcome, but we lack a solid justification for why. The issue is that we cannot justify how our future actions would affect past decisions, yet this appears to be the case. C.S. Lewis provides this justification.

Still, I wrote earlier that I was interested in how Newcomb’s problem reflects reality. First, I should note that I accept the phenomena described by Dostoyevsky. Some people indeed collapse into mental and physical illness over guilt, and it seems reasonable to interpret guilt as a manifestation of some divine moral law. Moreover, history offers many instances of spiritual transformation. One can find these phenomena in the writings of William James or Carl Jung, among the fellows in Alcoholics Anonymous, or in the Johns Hopkins Psilocybin experiments. If the reader accepts these accounts, we can explore Dmitri’s salvation with the expectation that his fictional story bears some reflection on our nonfictional reality.

A quick review may be in order. I’ve proposed the following claims: (1) People have an inherent nature or essence; this can be understood as a soul. (2) There is a necessary distinction between eternal and temporal realms. (3) The soul dwells in eternity, and the person exists in temporality. (4) The soul dictates what an individual likes or dislikes, and people generally make decisions in accord with their likes and dislikes. (5) When one makes decisions according to his likes and dislikes, his decisions are manifestations of his essence. (6) God has access to this essence in eternity and can make accurate predictions of decisions in temporality. (7) God's prediction determines an individual's salvation or damnation.

The case of Dmitri Karamozov adds a single caveat: his essence seems to change. I've introduced Dmitri Karamazov at an inflection point. He is found rambling incoherently to his cab driver, accepting his damnation and declaring his love of God anyway, and, finally, beginning a transition. Before this moment, Dmitri has lied, cheated, stolen, and engaged in continual promiscuity. He has lived most of his life overcome by lust and debauchery. That is, he has manifested every symptom of a sinful soul.

But, here, in the back of the cab, he makes a different decision. By committing to faith, despite all evidence of his damnation, he seems to shift his very essence. This shift implies that (8) our temporal actions can affect our eternal essence. If so, it would then affect the omniscient being's judgment. From a position of temporality, one may interpret this phenomenon as a present action affecting past circumstances. But, as C.S. Lewis told us, "ye cannot in your present state understand eternity." So this interpretation is flawed. Instead, present actions affect eternal circumstances, and salvation certainly justifies Dmitri's 1-Box extremism.

Conclusion

I began with three initial assumptions: (1) That Newcomb's Problem can be reinterpreted to fit the Calvinist Predestination Doctrine, but with a slight twist. (2) The symptoms of one's eternal fate can be felt well before death. And (3) The Brothers Karamazov provides access to spiritual phenomena that are difficult to evaluate directly.

I then noted that the younger Karamazov Brothers, Ivan, and Alyosha, fit nicely into the 1-Boxer and 2-Boxer dynamic. Their character arks allowed for an examination of both Boxisms and their consequences. From this, I arrived at the same conclusion as Nozick: 2-Boxers are correct that our current actions do not affect past decisions, and so it seems reasonable to use the domination principle. But the 1-Boxers are saved, and the 2-Boxers aren't. So, although the 2-Boxer argument seems logically sound, it is in some way flawed.

Then I proposed an additional assumption: the existence of an eternal and temporal plane, where God (the omniscient being) exists in the eternal, and humanity exists in the temporal. Therefore, he judges our essence in its eternal aspect, and humanity encounters the consequences temporally. This explanation accounts for the universal success of the omniscient being and the appearance of determinism.

Still, the temporal-eternal distinction leaves humanity in a state of apparent determinism, where temporal actions are dictated by eternal realities. But this illusion is broken by the phenomenon of spiritual transformation, which shows that temporal activities can change eternal circumstances. Importantly, this explanation justifies Dmitri Karamazov's 1-Box Extremism and, in some ways, the Calvinist doctrine of predetermination. It also accounts for the appearance of reverse causality, which is an understandable misinterpretation of the events.